Reinventing the General Plan

A Project of the California Planning Roundtable

With support from the American Planning Association, California Chapter

Great Model: City of Orange

Featured Principles: Manage Change, Build Community Identity, Prioritize Action

- Context

- Context-Based Planning to Guide Change

- Breakthroughs through Collaboration

- Built for Action

- Challenges and Lessons Learned

- Background Information

The City of Orange General Plan update was initiated in 2004 following years of significant change in the city and growth in the region. Since the previous General Plan’s 1989 adoption, much of the city’s remaining agricultural and undeveloped land had been urbanized. The area surrounding Orange had also become largely built-out. The city was experiencing problems with traffic congestion, aging commercial corridors, underutilized commercial property, housing demand, and a growing population. This update was adopted in 2010.

In the late-1990s, the one square mile historic Orange downtown core was designated a National Register Historic District, and commuter rail was introduced. Major institutions in Orange, including Chapman University, UC Irvine Medical Center, St. Joseph Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Orange County were experiencing immense growth and expansion. The City appreciated that these institutional expansions represented a great opportunity for Orange, bringing new activity and vitality to key areas of the City, but there were also issues, including the impact of University expansion on neighborhoods. Meanwhile, community priorities were also changing. A key goal was to capitalize on opportunities presented by institutional expansion while striking a balance with the City’s desire to preserve its sense of history and evolution, respecting the distinctive character of its diverse neighborhoods and business districts. The city sought to maintain diversity, while weaving connections that resulted in greater community cohesiveness.

The Orange General Plan uses all of its elements to guide change in a manner that reflects the diverse districts within Orange. Planners collaborated with other departments and agencies throughout the General Plan update, and in doing so both built credibility for planning and created a document designed for effective implementation. Through the General Plan process, planners realized that in order for the community and other City departments to be more invested in the planning process, the Plan had to resolve important issues and had to be designed for implementation.

The Orange General Plan shows how planning can be a vital tool for embracing change while protecting a community’s character. At the onset of the General Plan Update effort, the planning team embraced the notion that change is inevitable; the City is going to change, and the task at hand involved charting a course for where and how it is going to change in a manner that maintains and improves quality of life in the community.

While the surrounding area has become increasingly characterized by suburban sprawl, Orange has successfully worked to maintain its historic charm. The General Plan needed to honor and build upon the unique history and diverse character of Orange, and protect the distinct characteristics that have always made Orange a desirable place. A key goal for the City was to strike a healthy balance between the City’s historic and neighborhood preservation efforts and the expansion of institutions and growth in the region. In addition to regional growth pressures, the expansion of Chapman University and the medical centers created unique issues and opportunities.

The City of Orange looked beyond its city limit when crafting its Land Use Element and associated Land Use Policy Map to what was happening in the adjacent cities and unincorporated areas. Two unincorporated pockets of land, El Modena and Orange Park Acres, are located within the City of Orange Sphere of Influence, and the incorporated City of Villa Park is entirely surrounded by the City of Orange. The interface with adjacent jurisdictions presented interesting dynamics, particularly the City’s shared jurisdictional boundary with the City of Anaheim where large scale growth is occurring. The City of Orange land use program included intensification and a new urban mixed use land use designation for the West Katella Corridor and Uptown Orange area, both adjacent to Anaheim’s highly publicized Platinum Triangle district surrounding Angel’s Stadium, the Honda Center sports arena, and planned Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center. While the Orange General Plan was under development, there were ongoing adjustments, changing development assumptions, and General Plan Amendments that occurred for the Platinum Triangle in Anaheim. Therefore, the relationship between Orange’s West Katella Corridor and Uptown Orange land use focus areas and the Platinum Triangle generated significant discussion between the two City’s Traffic Divisions about the appropriate level of intersection and roadway analysis, and fair share contributions toward circulation improvements.

The Plan proactively plans for change by balancing “smart” urban development patterns with the protection of historical resources and community character. The Plan emphasizes economic development, allowing the City to take advantage of its location within the emerging North Orange County regional urban context, while also reinforcing existing neighborhood character and protecting environmental resources.

Change is anticipated; how that change will take place, and how substantial it will be, depends on the existing context. The plan anticipates that Orange will have a wide variety of districts. For example, the plan provides for immense diversity in housing options, including homes in the largest historic district in Southern California, semi-rural equestrian homes close to nature, suburban tract homes designed and developed by Eichler Homes and densely populated urban neighborhoods near public transit, cultural, and recreational activities.

The General Plan is intended to serve as a development manual for emerging urban nodes in a classic suburban community. The General Plan includes three new optional elements more characteristic of an urban than suburban environment: urban design, infrastructure, and economic development. The Plan is intended to aid in the transition of key parts of Orange from a suburban to urban character and to address development pressure on the periphery of the city. The Plan includes shifts in land use designations on the Land Use Policy Map, and also includes policies and implementation techniques in other General Plan elements to ensure successful outcomes. The key strategies that the General Plan uses to balance growth and preservation include a context-sensitive blend of historic preservation, infill planning, and support for more urban development.

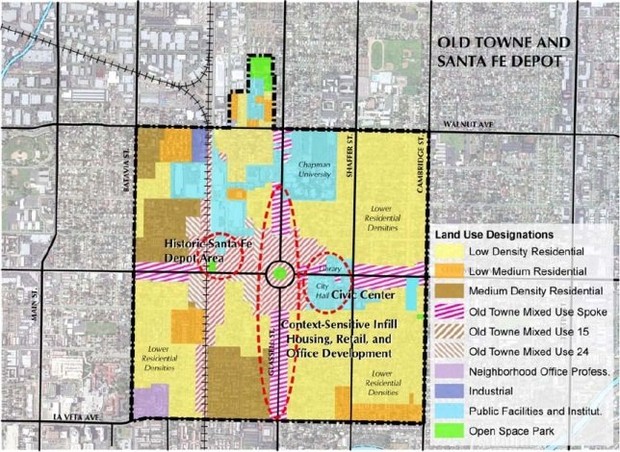

Historic Preservation: The City’s Old Towne Orange Historic District comprises approximately one square mile, and includes approximately 1,300 historic buildings dating from the 1880s to 1940. While the majority of these buildings are residential structures, the historic district also has a significant concentration of commercial and industrial buildings, many of which are linked to the early citrus industry, including packing houses and the Orange County Fruit Exchange, which ultimately became well-known Sunkist. At the heart of the Old Towne Historic District is the City’s historic downtown business district, with a distinctive central plaza.

In addition to the Old Towne historic district, there are three Post–War Eichler Home Tracts that are identified in the General Plan: the Fairhaven Tract, the Fairhills Tract, and the Fairmeadow Tract. Collectively, these tracts include approximately 340 Eichler homes in 0.15 square miles of the city. The Plan proposes to establish three Neighborhood Character Areas, one of which is specifically crafted to protect the Eichler homes. The Historic Preservation and Cultural Resources Element takes recognition of the Eichler Tracts as Neighborhood Character Areas a step further, and points to the potential future designation of the Tracts as a local historic district. The City plans to designate the Eichler Tracts district within the next year. This represents the first formal acknowledgement of distinctive Post-War development as being important to the culture and identity of the community.

In addition to Old Towne and the Eichler Tracts, there are approximately 375 scattered historic farmhouses and structures associated with former communities and settlements dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The General Plan recognizes the importance of these resources, and the Cultural Resources and Historic Preservation Element identify the need to establish Neighborhood Character Areas to protect the these areas.

The General Plan seeks to extend the City’s rich historic preservation toolkit beyond its traditional focus on Old Towne, and to make best use of the next generation of historic preservation tools. The Historic Preservation and Cultural Resources Element and related background documents provide the City with the policy tools needed to more effectively and consistently evaluate projects affecting historic properties. The City has conducted a Historic Resources Inventory as part of the General Plan implementation. Before the General Plan update, the City did not have a formal process for adding properties to the Historic Resources Inventory or changing the status of a property. The City plans to adopt a new process within the next year. The City can now draw from its historic context statements, updated Historic Resources Inventory, and Historic District Records for project analysis and CEQA impact determinations.

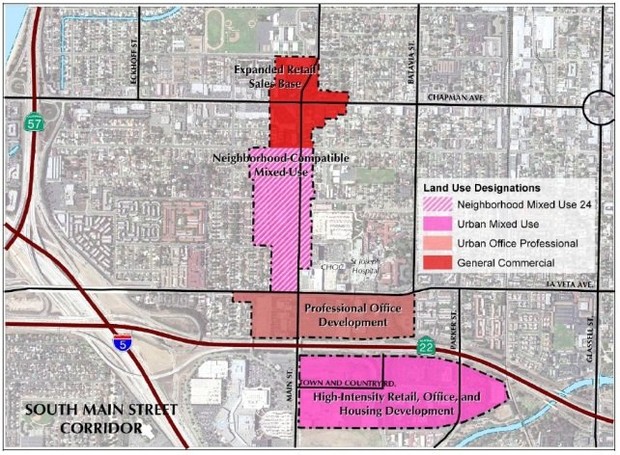

Infill Planning Based on Context: The General Plan establishes five new mixed-use designations in areas previously designated for commercial or industrial use. The General Plan is unique in that the mixed-use designations are context sensitive.

Each mixed-use designation is designed to be applied to specific locations and to complement its surroundings, particularly corridor development adjacent to residential areas. The designations range from “Urban Mixed Use” for the most dense areas, “Neighborhood Mixed Use” (meant to be compatible with adjacent neighborhoods), and three historic “Old Towne Mixed Use” designations with different density and structure types. These districts are good models for other communities with similar existing development diversity seeking to incorporate context-sensitive mixed use.

In crafting the new mixed-use designations, the City did not view the city limit as a “wall,” but rather considered how Orange might benefit from activity in neighboring cities. This is most evident in the City’s new Urban Mixed Use land use designation. This designation was applied to areas of Orange with concentrations of existing major employers, easy access to transit, and infill or redevelopment opportunities. In evaluating suitable areas, the City looked to the neighboring Cities of Santa Ana and Anaheim. In one instance, the proximity of a park, bike trail, shopping mall, and commercial center with a grocery store in the City of Santa Ana convinced the planners that mixed use development could be implemented and successful. In two other instances, the analysis considered proximity to Angels Stadium, the Honda Center, potential rail facility and service enhancements, and significant mixed-use development in Anaheim’s Platinum Triangle.

Facilitating Urban Development: The City also used this context-based approach in other elements of the General Plan to reinforce the plan’s land use goals and create a more context-sensitive regulatory framework to enable more urban development. The best example of how the City is facilitating more urban development is the General Plan’s new noise standards for mixed-use and multi-family residential land uses located along major arterials. The General Plan encourages higher-density residential and mixed-use development (Economic Development Policy 3.4), as well as attractive and vibrant commercial and mixed-use corridors (Urban Design Goals 1.0 and 2.0). The City recognized that noise standards needed to be amended to make residential development feasible along the City’s main arterials and in mixed-use environments. In these areas, a higher level of ambient noise should not necessarily be a deterrent, when considered in the context of other benefits of an urban neighborhood, and where sound walls and balcony enclosures are not a desirable option. The previous Noise Element had relied on the State guidelines to determine noise impacts and compatibility, which are generally associated with a suburban atmosphere. The new standards identify acceptable and conditionally acceptable noise levels, while accounting for more urban environments. Orange’s modified noise standards have already been employed by other jurisdictions facing similar challenges.

Through extensive collaboration, the Planning Department arrived at a series of “break-through” moments that built credibility for planning with other City departments and demonstrated that the value of the General Plan goes beyond land use planning and development issues. By working with other departments and agencies early on, the General Plan process became a vehicle for resolving long-standing policy inconsistencies and laid the foundation for the ongoing communication needed to effectively implement the Plan. In addition, the plan also promoted looking outside of the city limit allowed for a more comprehensive approach when planning for the future of Orange.

The General Plan process included a deliberate effort to engage City departments beyond Planning, recognizing that successful pursuit of the Community Vision Statement and General Plan goals was largely dependent on their buy-in and activities. As a first step, planners worked closely with colleagues from other departments to determine whether and how individual departments were referencing the General Plan in their daily work. This allowed planners to ensure that the content of the updated General Plan would accurately reflect the role of the departments involved in implementing each element.

An example of this collaboration is the update of the Urban Water Management Plan and Sewer Master Plan Update. For the first time, Public Works and Planning staff collaborated to develop growth and development assumptions. While the Public Works Department had planned to base development assumptions on past development patterns and trends, Planning staff provided guidance regarding the new development paradigm for the future of Orange. The built-out nature of the community, combined with the infill orientation of the General Plan land use program, represents a fundamental shift away from previous approaches to infrastructure planning that focused on suburban, greenfield development patterns. The new development assumptions considered that future residential growth would largely be concentrated in the western portion of the city, which had been traditionally in commercial use, and recognized that future residential growth would occur in the form of multi-family development at much higher densities than the Urban Water Management Plan had previously considered.

By using the General Plan update as an opportunity to resolve long-standing policy issues and integrate issues that had previously gone unaddressed, planners were able to build support for the Plan over the course of its development. A significant outcome of the General Plan update was the acknowledgement and reconciliation of internally conflicting policies in the Circulation and Historic Preservation elements of the 1989 General Plan. For instance, roadway classifications in the 1989 Circulation element called for the widening of two major street segments in the heart of the City’s Old Towne Orange National Register Historic District. Such a widening would have significantly impacted the Historic District.

The City initiated discussions with the Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) to explore the possibility of reclassifying these sensitive street segments. OCTA’s role was critical as the keeper of the County Master Plan of Arterial Highways (MPAH). So long as the City could demonstrate adequate traffic flow, OCTA was open to the possibility of downgrading roadway classifications and thereby reducing ultimate right-of-way widths. City and OCTA staff worked closely over several months, ultimately downgrading the roadway classification on the County MPAH. Following OCTA Board approval of the re-classification, the first implementation action of the 2010 Orange General Plan was to amend the City’s Master Plan of Streets and Highways to downgrade the roadway classification of the two Historic District street segments, and ensure protection of the Historic District into the future.

The City of Orange General Plan is built for action, and provides an example of how to structure a “work program” guiding all City decision-making activity. Through the implementation of the General Plan, the City has found that the community has a greater recognition of the relationship between the Plan and the implementation of successful City projects, and community members have acknowledged the City’s commitment to the General Plan. The Plan includes an extensive implementation plan designed to guide City elected officials, commission and committee members, staff, and the public to put the General Plan into daily practice. The work program translates goals and policies from general ideals to specific actions. Each implementation program requires City action, either alone or in collaboration with other organizations or federal and state agencies. For each program, the related General Plan policies are listed, along with the responsible party, recommended time frame, and likely funding source. Some of the implementation programs are day-to-day procedures (such as review of development projects), and others require new programs or projects. In some cases, elements of the implementation programs may carry through to individual departments’ work plans or the City’s Capital Improvement Program (CIP).

The credibility that the Orange General Plan has built for planning has gone beyond the update process to the implementation phase. Since adoption of the General Plan, the planning team has found that there is greater recognition, both on the part of City staff and the public, of the relationship between successful City projects and General Plan implementation. According to City staff, members of the public, Planning Commissioners, and City Council members now frequently ask, “Is this implementing the General Plan?” when discussing City projects and programs. Examples of projects and programs since the General Plan was adopted include completion of the Santiago Creek Bike Trail, establishment of railroad Quiet Zones, down-zoning of neighborhoods in the Old Towne Historic District, and updating of the City’s Urban Water Management Plan and Sewer Master Plan. Community members have expressed satisfaction with these projects, and have recognized the City’s commitment to the General Plan.

Within the Plan, implementation programs are presented in a separate appendix, and were adopted by a separate, but related, resolution to the General Plan. This allows the City to modify implementation programs to meet changing community conditions, resources, and priorities without needing to process a General Plan amendment.

The implementation programs are used to prepare the Annual Report to the City Council on the status of the City’s progress in implementing the General Plan, as described in Section 65400 of the Government Code. Many of the individual actions and programs also act as mitigation for environmental impacts resulting from planned development in accordance with the General Plan. Therefore, the Annual Report is also used to monitor application of General Plan Environmental Impact Report (EIR) mitigation measures as required by Public Resources Code Section 21081.6.

Prior to adoption, Planning Department staff began using the General Plan and implementation programs to review proposed projects, an important feedback loop that amplified the quality of the Plan. The City has worked to connect every staff report that the City Council reviews with General Plan implementation, and has conducted outreach with department heads to remind them about how the General Plan programs should overlap with their work plans each year so that the City does not lose sight of its long-range goals.

As part of the City’s Budget and CIP process, City departments are asked to review the General Plan Implementation Plan when developing work plans for the coming year or identifying capital improvements. The City’s CIP project sheets include a field that references the applicable General Plan Element. More detailed information is included as a matrix in an appendix to the CIP that details the goals, policies, and implementation programs applicable to individual projects.

Challenges

- Learning Curve. Perhaps the biggest challenge faced in the General Plan update was the learning curve within the City organization and the general public regarding the purpose and importance of the General Plan. Significant amounts of time were spent working with other City departments about the best means to accurately and strategically present the goals, policies, and plan of each element for the benefit of the departments’ functions. A lot of time was also devoted to explaining how the document could be used as a tool to pursue long-term City goals.

- Building Trust. In some instances, individuals and community groups expressed feelings of fear and resistance to the Plan, or a feeling of mistrust in the development of the Plan. Related to this challenge was a need to overcome the perception that the General Plan was solely a land use plan. Breakthroughs were realized through demonstrating circumstances where community benefits could be satisfied by leveraging the Land Use Element along with one of the other General Plan elements. Since General Plan adoption, implementation has built credibility for the Plan as well as Planning staff.

- Late Changes. Political dynamics also proved to be challenging at different points along the way. Policy makers reserved their feedback throughout Plan development. Over the years the Plan and EIR were drafted, there was a change in the composition of the City Council. Consequently, the City Council and Planning Commission requested significant changes to the preferred land use plan that required revisions to the draft Plan and EIR shortly before the release of the documents for public review. Associated with these revisions were additional unanticipated consultant costs. A change in corporate ownership, along with the elongated project schedule, resulted in extensive re-negotiation of the contract and budget with the consultant. The City is now focusing on reducing future costs associated with the General Plan. By keeping the General Plan up-to-date, the City hopes to avoid the need for a large overhaul in the future. In the context of the recent economic downturn and decreasing City budgets, planners are focused on keeping the Plan relevant, which helps to justify the use of funds for the General Plan.

- Conflicts of Interest. Hearings were further complicated by the fact that members of both the Planning Commission and City Council had conflicts of interest with some of the land use alternative focus areas, complicating the review and deliberation about land use changes. The City’s strategy for managing these conflicts and navigating the public hearing process was complex, but effective. Specifically, during the hearing process, each of the seven land use focus areas was broken out for individual discussion, with the conflicted member(s) of the Planning Commission and City Council recusing themselves from that particular focus area discussion. After discussion and deliberation of each focus area, the participating members took a “straw vote” on that particular area. The final City Council action on the Plan reflected the outcome of the “straw votes,” with the City Council Resolution presenting each land use focus area separately. While this method of deliberation was successful, the narrow focus of discussion warranted the exercising of caution so as not to lose sight of the “big picture” land use plan, and the relationship of focus area land use policy with other General Plan Element content.

- Collaboration with other Agencies. The greatest challenge associated with coordination with other agencies was the reality that planning for the future, more often than not, is confined to jurisdictional boundaries. It is a city’s purpose to protect its own interests, and put plans in place that lead to the best possible outcome for its community. While Orange looked to development conditions and community amenities in neighboring cities as opportunities and assets that influenced the crafting of land use policy, the Orange General Plan Update effort did not involve active collaboration with, or input from, adjacent jurisdictions beyond the subject of traffic and circulation. The primary focus of input from Anaheim, Santa Ana, Garden Grove, and Tustin was on traffic impacts to intersections and roadways. This was particularly the case with Anaheim’s Platinum Triangle area, which is an area surrounding Angel’s Stadium that is planned for significant mixed-use, residential, and office development.

An outside agency success story was the City’s collaboration with the Orange County Transportation Authority on working toward the downgrading of historic district roadway classifications on the County Master Plan of Arterial Highways.

Lessons Learned

The Orange General Plan model offers the following lessons:

- Investing time and energy in working with City colleagues in other (non-Planning) departments to develop a better understanding of the purpose and potential of the General Plan is well worth it. This collaboration can lead to the realization that there are shared goals, and that practical, creative approaches to dealing with past General Plan “problem areas” can be resolved with minimal or no organizational friction. Through this effort, at the end of the process you will have established relationships that lead to others helping to champion and implement the General Plan.

- Time and energy working with the public is essential to the project, and planners should be prepared for skepticism or resistance among community members. The process could benefit greatly from political support at the start, with decision makers generating informal excitement and interest through their conversations with residents and business persons.

- When developing your project budget and scope of work, plan for a significant contingency. It would also be beneficial to incorporate language in the initial contract addressing the issue of billing rates should the project experience an unanticipated elongated schedule due to factors beyond the consultant’s control.

- To avoid additional costs and time in the plan preparation, a strategy for engaging City policy makers early in the General Plan effort is critical.

Community Description

The City of Orange, incorporated in 1888, is the third oldest city in Orange County, after its neighboring cities of Anaheim and Santa Ana. It is also the County’s third largest City.

The City of Orange is characterized by highly diversified land uses, including semi-rural equestrian neighborhoods, one of the largest historic districts in the western United States, contemporary tract housing, heavy and light manufacturing, historic neighborhood commercial districts, regional malls, three major regional medical institutions, and a major university. This diversity of uses provides for a range of employment opportunities and resident citizens. The City of Orange jobs-housing ratio is second among the largest cities in the County.

Among its peer group of older Orange County cities, Orange’s population is predominantly Caucasian, but shares a higher concentration of Hispanic residents. While its Asian population is at a level similar to that of Santa Ana, it is notably lower than other large Orange County cities. The Orange population shares a median age and household size similar to most other Orange County cities. The housing tenure is 60% owner and 40% renter.

Community Characteristics

|

|

Orange |

Santa Ana |

Fullerton |

Anaheim |

Irvine |

|

Incorporated Area |

35 square miles |

27 square miles |

23 square miles |

50 square miles |

66 square miles |

|

Population |

128,821 |

337,977 |

126,003 |

328,014 |

217,686 |

|

Median Age |

33.2 |

26.5 |

32.9 |

30.3 |

33.1 |

|

Housing Units |

44,627 |

75,943 |

47,209 |

103,242 |

81,011 |

|

Average Household Size |

3.16 |

6.64 |

2.89 |

3.39 |

2.79 |

|

Total Employment |

107,451 |

167,902 |

70,775 |

179,049 |

196,736 |

Population Ethnicity

|

|

Orange |

Santa Ana |

Fullerton |

Anaheim |

Irvine |

|

White |

54.6% |

12.4% |

48.7% |

35.9% |

57.0% |

|

Hispanic |

32.2% |

76.1% |

30.2% |

46.8% |

7.4% |

|

Asian & Pacific Islander |

9.4% |

9.0% |

16.2% |

12.3% |

29.8% |

|

Black |

1.4% |

1.3% |

2.1% |

2.4% |

1.4% |

|

Other Races |

2.4% |

1.2% |

2.8% |

2.7% |

4.4% |

Timeframe of Plan Development

6 years

Keeping on Track

The actual schedule far exceeded the originally expected schedule. Factors that prolonged the schedule included the significant “learning curve” during the public outreach process explaining the fundamental purpose of the General Plan and how it relates to quality of life aspects of the City beyond land use.

During Plan development, the subject of climate change emerged as a topic needing to be addressed in the General Plan and EIR. The planning profession was still developing a preferred manner in which to address this issue in comprehensive planning efforts and environmental review. Exploration of this issue by the City staff and the consultant added to the project schedule, and was complicated by local political perspectives on the subject.

The project schedule was affected by a lack of direct feedback during Planning Commission and City Council briefings and study sessions. Policy makers offered limited input earlier in the process, as the details of the preferred land use plan were being developed. It was not until a final study session conducted prior to the release of the General Plan and DEIR for public review that the Commission and Council provided definitive feedback that resulted in the need for land use changes and associated changes to technical studies and EIR analysis.

This significant development also led to a request from the City’s consultant for a budget amendment. In conjunction with this request, the consultant experienced a change in corporate leadership resulting in the need for re-establishment of the project contract. The additional work effort and change in billing rates due to the prolonged project schedule resulted in a further delay due to negotiations between the City and consultant.

Public Participation and Stakeholder Involvement

The public process engaged a broad cross-section of the community, including developers and commercial property owners/representatives, institutional representatives, community members experienced in the public process, and residents not yet familiar with community planning issues and processes. In addition to the complexities of the community participation were unpredictable and dynamic political influences. The Supreme Court ruling on Eminent Domain (Kelo v. City of New London) also occurred on the day of a key public outreach event, creating a high level of anxiety among members of the public.

Community Workshops: An extensive public outreach effort occurred during 2005. Publicity for the outreach effort was provided on the City’s website and cable television channel, specially designed bookmarks distributed at the City’s three libraries, notices posted at coffee houses throughout the City, and direct mailing to property owners in the original nine focus areas of the City where land use changes were being considered. Six community workshops were held, including youth, seniors, and the community at large. The workshops occurred at locations throughout the City. Workshop attendance ranged from approximately a dozen to nearly 200 participants. The input received at each workshop informed the development of the Community Vision Statement, land use alternatives, and goals and policies.

General Plan Advisory Committee: A General Plan Advisory Committee (GPAC) comprised of 15 diverse members of the public met nine times during 2005. GPAC workshops began with a bus tour of the entire city. Subsequent workshops involved close work with community workshop feedback, and consideration of possible land use alternatives. The GPAC participated in a consensus-based process to craft the final Community Vision Statement and draft goals and policies for the General Plan, which appear in the draft General Plan much as they were originally crafted.

General Plan Website: The City’s General Plan website was the subject of significant interest, with the site receiving over 10,300 visits by the start of the public hearing process for adoption. The site served as a key source of project information, as well as an additional means for the public to provide input on the project.

Other City Departments’ Involvement

Early phases of the project involved extensive information gathering from, and reconnaissance meetings with, City departments. The purpose of these meetings was to develop an understanding of the degree to which individual departments actually used the 1989 General Plan, assess the accuracy of the content of the 1989 elements, and build relationships with outside agencies. The benefits of working with other departments have extended beyond adoption of the General Plan. The General Plan is now tied to Master Plan development for sewer and water utilities, whereas previous Master Plans were developed separately from the General Plan. More departments are now considering the General Plan and how their projects accomplish the goals of the General Plan.

Legal and Policy Context

The General Plan Update was motivated by the need to refresh a 20-year-old document. At its onset, there was no legislative motivation. However, after project initiation it became clear that climate change was an issue that needed to be incorporated into the Plan. Staff was also thinking proactively about federal and state Complete Streets legislation and the City’s NPDES permit in the drafting of certain aspects of the Circulation and Mobility Element, Natural Resources, and Infrastructure Elements.

Consideration of Regional Issues

The land use alternatives and content of the Circulation and Mobility Element, Housing Element, and Urban Design Elements were influenced by regional long-range transportation plans involving expanded rail service and new bus rapid transit (BRT) service. Specifically, two of the three Urban Mixed Use districts in the General Plan’s land use program are concentrated around existing established regional bus service corridors, and in proximity to the Anaheim Amtrak/Metrolink Station and potential future Anaheim Regional Intermodal Center. A BRT corridor is also planned for the State College Boulevard Corridor that runs through Orange and cities to the north and south. These transit corridors run through major regional uses and employment centers in Orange (hospitals, County social services, office, and shopping mall), and major uses in Anaheim (Angel Stadium, Honda Center, planned Platinum Triangle residential and office development, Santa Ana River Trail) and Santa Ana (shopping mall, Discovery Science Center, Bowers Museum, Santiago Creek Trail).

The General Plan content is also aligned with regional sustainable communities planning and greenhouse gas emission reduction efforts. By creating new mixed use land use categories, the Plan promotes more urban infill settings.

As described in the “Context-Based Planning to Guide Change” tab, the City of Orange participated in interactive discussions with staff in adjacent cities on the subject of potential traffic impacts.

Community Reaction

Community reaction varied at different points in General Plan development and adoption. These dynamics often made it difficult for planners to effectively engage members of the public, and led to confusion regarding the General Plan during the hearing and adoption process.

At the onset, community reaction was largely neutral due to the lack of familiarity with the General Plan as a guiding policy document for the City. As the effort progressed and focus areas were identified for land use changes, property owners in the affected areas engaged in the process. Those owners with property experiencing significant use changes (e.g., Industrial to Medium Density Residential) or reductions in potential density or floor area ratio responded negatively.

Open space advocates participating in the process expressed a concern that more should be done to find ways to create new open space opportunities. Due to the built-out nature of the City, it was not possible to address this issue to their satisfaction, as the establishment of new open space and recreational opportunities would only be possible through the conversion of already developed or entitled private property.

There was also negative reaction from property owners in the City’s historic district stemming from a perception that the General Plan’s intention was to redevelop the historic district. This was not the case; rather, the General Plan reduced densities in the neighborhoods of the historic district, strengthened City policy regarding adaptive reuse and protection of historic buildings, and downgraded roadway classifications to safeguard the historic district. Through the implementation of the General Plan, as people see evidence that the General Plan has resulted in increased protection for historic districts, the City has built more credibility for planning within the community.

Since adoption of the General Plan, planners have found that there is greater recognition among the community of the relationship between the General Plan and the implementation of successful City projects. Community members have expressed satisfaction with several City projects, and have acknowledged the City’s commitment to implementing the General Plan.

Implementation Features

As a starting point, the General Plan Implementation Plan provides direct references to specific goals and policies in individual elements, and explains the relationship between the General Plan and the City’s organizational Strategic Plan as well as the Mission Statements of individual City departments.

Connection to Jurisdictional Budget

Planning staff has developed a General Plan Implementation Matrix that is intended to guide and inform City department work plans included in the City Budget. This represents the first time that the City will refer to the General Plan Implementation Plan for work plan development.

A General Plan implementation is also addressed in City’s Capital Improvement Program with information included on individual project description sheets, as well as an implementation matrix included as an appendix to the Capital Improvement Program.

Adaptability

Throughout development of the General Plan, the City has been committed to ensuring that the Plan remains “current” and relevant. Planning staff has implemented annual reviews of the General Plan elements with all City departments to confirm that information contained in the elements remains accurate and relevant. This annual review provides regular opportunities to make adjustments to the Plan so that it is representative of changes to physical conditions, transportation options, land use market demand, infrastructure advancements, and community demographics. Because the City of Orange is a built-out community, changing conditions are expected to come about through land redevelopment, economic dynamics, and the needs and expectations of community members.

Since adopting the Plan, the City has completed various projects, including the following:

-

Completion of the Santiago Creek Bike Trail

-

Update of the Urban Water Management Plan (adopted early 2012)

-

Update of the Sewer Management Plan

In addition, the following efforts are currently underway:

-

Planning staff and Public Works Traffic Division staff are collaborating to reconcile inconsistencies between the General Plan’s Circulation and Mobility Element and the Orange Municipal Code that came to light following adoption of the General Plan. Staff anticipates a Code amendment in late 2012 to resolve this issue.

-

Planning staff is collaborating with residents of the City’s Eichler Home Tracts in support of the residents’ effort to obtain National Register District status for the Tracts. Concurrently, the City’s Comprehensive and Advance Planning Work Plan for 2012-13 includes designation of the Eichler Tracts as local historic districts.

-

Planning staff has solicited input from other City departments to confirm the accuracy of information in the General Plan describing each department’s function. Completion of the clean-up items related to this review has been delayed due to limited staff resources, but is expected to occur by the end of 2012.

Accessibility

The General Plan and EIR are available on the City of Orange website through direct links from the City’s Home Page, a link from the Community Development Department website, and links to specific elements from the websites of individual City departments.

Printed copies of the General Plan and EIR are available at the City’s three public libraries as well as the City Hall Planning Counter.

Graphics and Presentation Quality

The Plan makes extensive use of planning graphics to illustrate key concepts, and policies and implementation programs are presented in clear, easy-to-understand prose free of jargon. One key example of this is a diagram that illustrates a development transect and intended uses for the City’s five mixed-use designations.

Organization

The General Plan addresses all of the state-required elements, organized under the titles of Land Use, Circulation and Mobility, Natural Resources, Noise, Housing, and Public Safety. In addition to the mandated elements, the Orange General Plan includes four optional elements, including Cultural Resources and Historic Preservation, Infrastructure, Urban Design, and Economic Development. Of the optional elements, Infrastructure, Urban Design, and Economic Development were new additions to the 2010 General Plan.

The General Plan elements were crafted specifically to be multi-disciplinary. The Introduction of each element explains how that particular element supports the Community Vision Statement, and also goes on to discuss the relationship between the element and other General Plan elements.

Costs

Original contract amount for the General Plan Update (including EIR) = $977,443

Final actual cost = $1,278,693

Adoption Process

The General Plan and EIR adoption process commenced with Planning Commission hearings in August 2009, which ended in November 2009. City Council hearings began in January 2010 and concluded in March 2010.

The public hearing process was complex at both the Planning Commission and City Council levels due to conflicts of interest among the members of the two bodies related to various land use changes in the eight Land Use Focus Areas. Consequently, review of the land use changes by each body had to be segmented to allow different combinations of member participation on each focus area.

There was also a significant level of public comment provided at the Planning Commission and City Council hearings on the project, including perpetuation of misinformation about the project that had circulated widely among the public. Dialogue between staff, the Planning Commission, and City Council was extensive with respect to presenting the details of the Plan and EIR accurately and diffusing Commission and Council skepticism.

As was discovered during the public outreach process during early stages of General Plan development, the Planning Commission and City Council were not accustomed to working with aspects of the City’s General Plan beyond the Land Use Policy Map. Therefore, considering the comprehensive components of the updated General Plan was somewhat unfamiliar. The Land Use Element received the majority of attention during the review process, with the Circulation and Mobility Element being discussed at length with respect to its relationship to the City’s Historic District. The remaining nine elements were the source of relatively limited discussion.

CEQA Review

CEQA review began as a straight-forward process, but became drawn out as a result of a significant change in the preferred land use plan by the City late in the General Plan and DEIR development process. Consequently, revisions were needed to the technical studies and EIR section content.

Original contract amount = $94,900

Final actual cost = $233,490

Legal Challenges

The General Plan did not face any legal challenges.

Planning Staff and Consultants

Alice Angus, AICP, Community Development Director, City of Orange

Anna Pehoushek, AICP, Principal Planner, City of Orange

Jennifer Le, Senior Planner/Environmental Coordinator, City of Orange

John Bridges, FAICP, Principal, AECOM

Jeff Henderson, AICP, Senior Project Manager, AECOM

Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc.

Alliance Acoustical Consultants

Chattel Architecture, Preservation, Planning

PAR Environmental Services, Inc.

Accessing the Plan

The City of Orange General Plan is available to the public in print at the Orange City Hall Planning Counter and at the three City libraries. The General Plan is also accessible on the City’s website at: http://www.cityoforange.org/depts/commdev/planning/general_plan.asp .

Name of Primary Point of Contact at the Jurisdiction

Anna Pehoushek, AICP, Principal Planner

Date Reviewed by Jurisdiction

July 19, 2012

CPR Peer Reviewers

David Booher, Linda Dalton, Al Zelinka

CPR Project Team

Elaine Costello, Project Manager; Co-Chairs Cathy Creswell and Janet Ruggiero; Alexis Mena, Project Assistant

The Catalog

Our catalog contains a number of General Plan "Great Model" examples. Browse the entire catalog

Browse by Principle

- Create a Vision

- Manage Change

- Make Life Better

- Build Community Identity

- Promote Social Equity and Economic Prosperity

- Steward and Enhance the Environment

- Engage the Whole Community

- Look Beyond Local Boundaries

- Prioritize Action

- Be Universally Attainable

Browse by tag:

awards city climate-change context county equity graphics growth-management health implementation infill mature-community organization participation preservation redevelopment region rural smart-growth suburban sustainability town urban urban-design web-strategies