Reinventing the General Plan

A Project of the California Planning Roundtable

With support from the American Planning Association, California Chapter

Great Model: City of Watsonville

Featured Principles: Promote Social Equity and Economic Prosperity, Steward and Enhance the Environment, Engage the Whole Community

- Context

- Planning through the Lens of Social Equity

- Compact Development to Support the Economy

- Engage a Diverse Community

- Challenges & Lessons

- Background Information

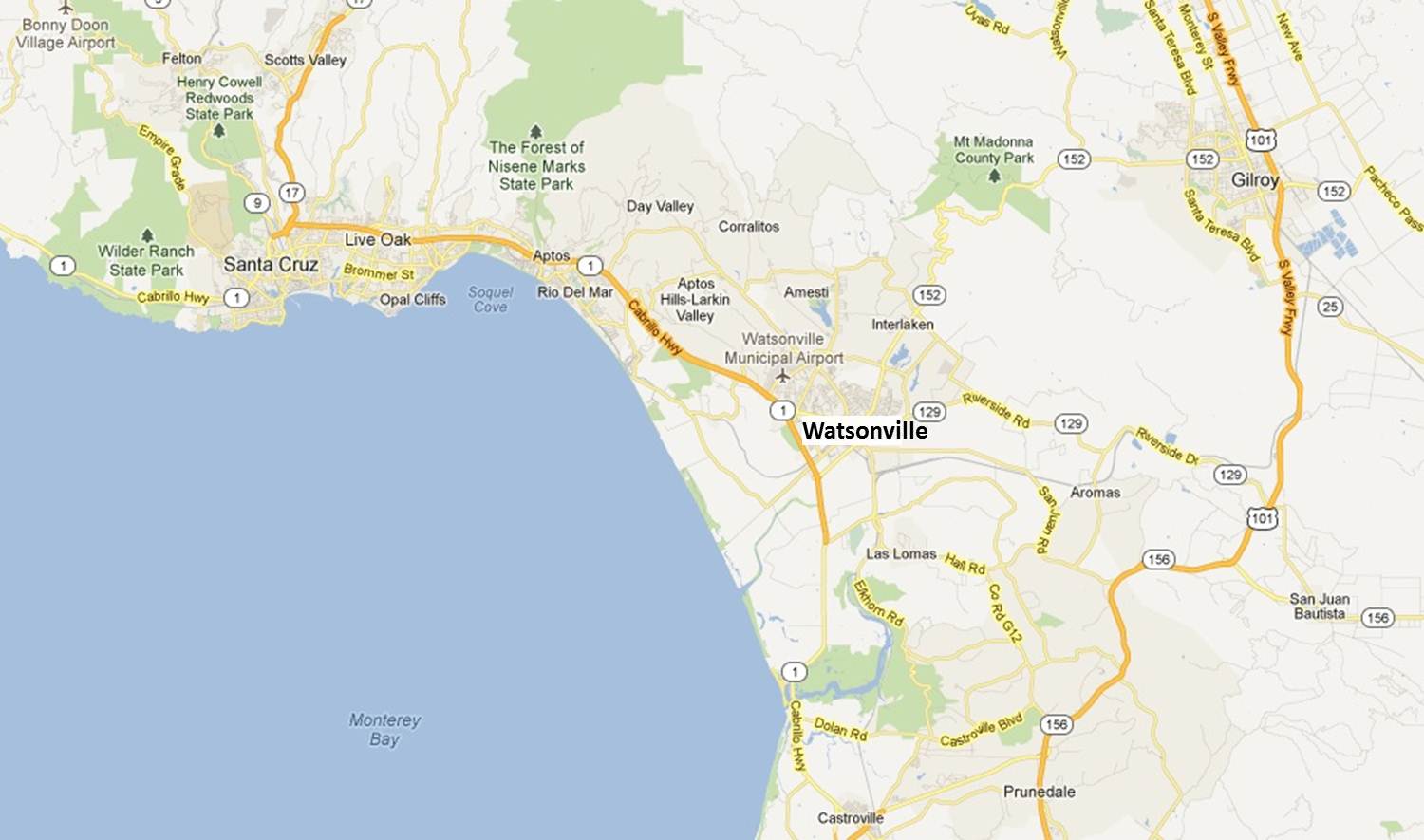

Anyone who has sipped apple juice or eaten a strawberry has probably had a taste of Watsonville. Until recently, Watsonville remained isolated from the San Francisco Bay Area, except as a source of food. Today, Watsonville faces new pressures for residential growth as it offers affordable housing within commuting distance of employment growth in Santa Cruz and Silicon Valley.

Compared with nearby communities and the State as a whole, Watsonville’s population is lower income and includes a larger percentage (81%) of Latino and Hispanic residents. Watsonville’s General Plan has embraced its diversity and agricultural assets. The Plan, dubbed VISTA (“VISion To Action”), responds to these issues in a way that few other cities have, by focusing on social equity and the local economy.

The development of VISTA 2030 began in 2003, shortly after the passing of "Measure U," a 2002 voter referendum that established an Urban Limit Line to protect productive farmland from development. VISTA 2030 was adopted in 2006, and was broadly supported.

However, shortly after the Plan was adopted, the city was sued because of concerns with the increased densities proposed for the Buena Vista area near the airport. The court found that the Plan and its EIR did not adequately analyze the impacts on aviation and should have included lower density alternatives.

The lawsuit ultimately resulted in the City rescinding the 2006 General Plan and engaging pilots and residents to arrive at a new land use plan for the Buena Vista area. All other policies in VISTA 2030 have remained in the revised Plan, which was adopted in January 2013.

Although the revised Plan is a work in process, the following aspects of VISTA 2030 will be preserved in the Plan, and provide valuable lessons. VISTA 2030:

- Makes social equity a central focus

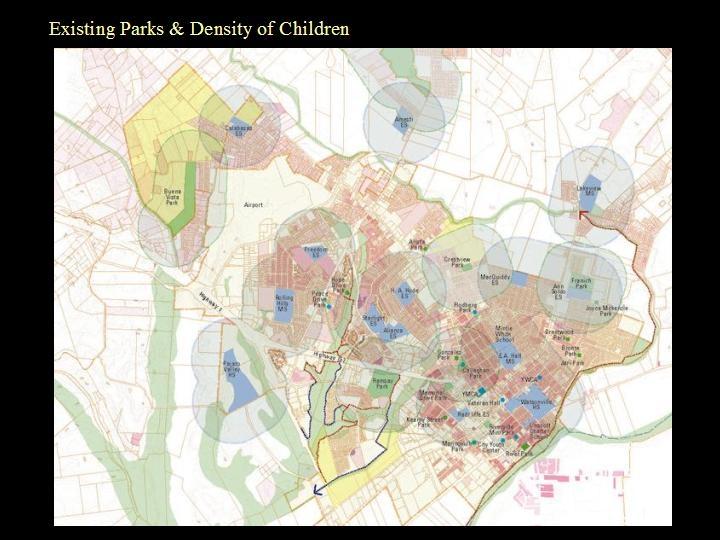

- Recognizes parks and recreational opportunities as critical for children and low-income families

- Uses compact development to preserve agriculture, thereby retaining jobs for low income residents

- Promotes walkability to strengthen neighborhoods and improve services for low income residents without cars.

- Reflects an inclusive, community-driven planning process

VISTA 2030 reflects all three “E’s” of sustainability – equity, environment, and economy – with social equity as a driving principle. Behind many of the General Plan’s policies is a recognition of the need to protect the jobs of low-income workers and provide services and amenities to Watsonville’s residents. A prime example of this is the General Plan’s approach to open space.

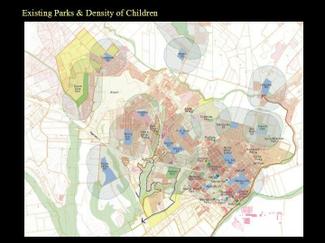

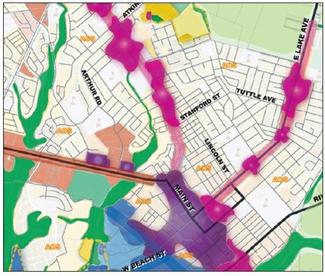

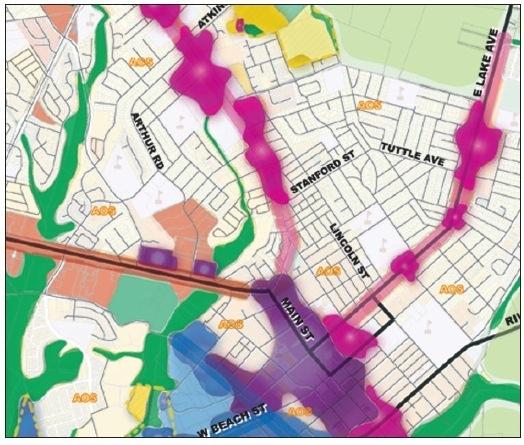

The General Plan process featured "greenprinting," which is the development of an open space creation and preservation strategy that considers existing physical conditions (e.g. habitat, existing parks, biking/hiking routes) along with criteria for where to target future investments (e.g. into underserved areas, to leverage habitat conservation along with recreation, to attain complete circulation networks). In Watsonville, the greenprinting process emphasized issues related to social equity. Underserved areas with higher concentrations of children and low-income households were prioritized for future park investments. "Council and others talked a lot about the walkable infill concept and its importance to low-income families. This was the basis for the parks [greenprint] that emphasizes investment in disadvantaged neighborhoods," said Keith Boyle, Watsonville's Principal Planner. The Plan emphasizes recreational opportunities by establishing an interconnected network of trails and, importantly, by planning new parks in disadvantaged low-income and minority neighborhoods.

Targeting park investments illustrates a larger strategy to serve and strengthen low-income neighborhoods. These neighborhoods have large minority and immigrant populations who face challenges. "We take a holistic approach to these traditionally disadvantaged areas," said Keith Boyle, "not just with parks but also code enforcement, crime enforcement, social services and frequent community-building meetings." The General Plan also emphasizes education and work programs to increase economic opportunities.

The City of Watsonville has realized that compact development and a walkable urban environment are imperative in order to maintain the agricultural economy that is the lifeblood of Watsonville’s workers. If not properly managed, Watsonville's growth could consume valuable farmland, thereby undermining the local economy -- trading today's working class jobs for tomorrow's suburban subdivisions. In Watsonville, the improvement of urban areas serves as a growth management tool to enhance the quality of life for Watsonville’s residents while protecting the agricultural areas that provide jobs to many of those same residents. VISTA 2030’s land use plan manages to simultaneously promote often competing goals related to agricultural preservation, housing needs, economic vitality, and social and economic diversity.

Watsonville voters established Measure U, which created the City’s Urban Limit Line (ULL), but it provided only an outline for how the Measure's vision of compact growth would be attained. One of the Plan’s goals was to work within the ULL while accommodating projected housing and employment growth.

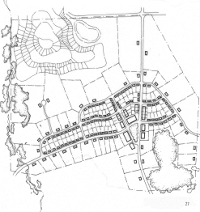

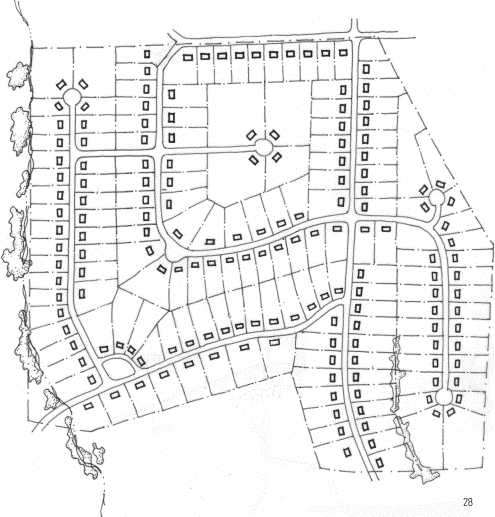

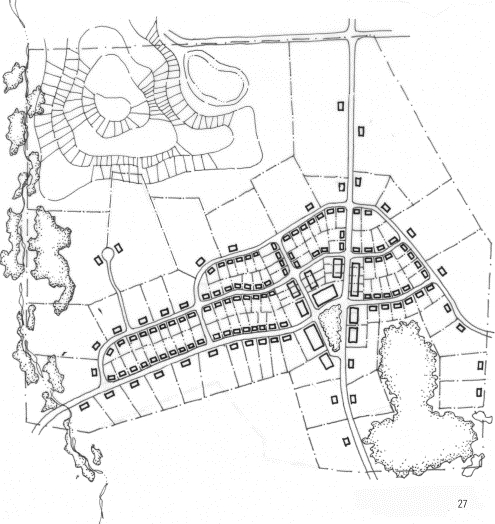

Farmland in Watsonville is not only protected by the City’s adopted ULL, but is recognized by the City’s General Plan as vital for the local economy. To preserve farmland while accommodating projected growth inside of the ULL, VISTA 2030 promotes a mix of moderate- and high-density housing types, such as single-family houses on small lots, townhouses, small apartment buildings, and – where transit access is best – larger higher-density options (within the urban limit line). The Plan calls for minimum average densities for new growth areas of about 10 units per gross acre. Along arterial roadways and in the downtown, the Plan calls for a minimum average residential density of 25 dwelling units per acre.

A mix of housing is not only more compact than would otherwise occur, but urban densities also support the availability of "walk-to conveniences" – such as food stores, local shops and services, and parks – that are necessary for households without cars that rely on pedestrian access. The Plan calls for sidewalks, tree-lined streets and street-facing buildings to make the path between home and these conveniences attractive. Higher densities also sustain more frequent transit service than would be possible with low densities.

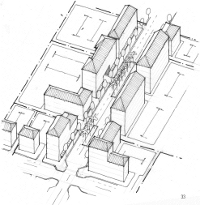

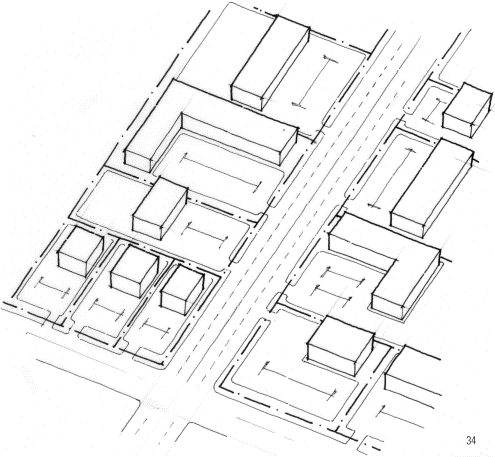

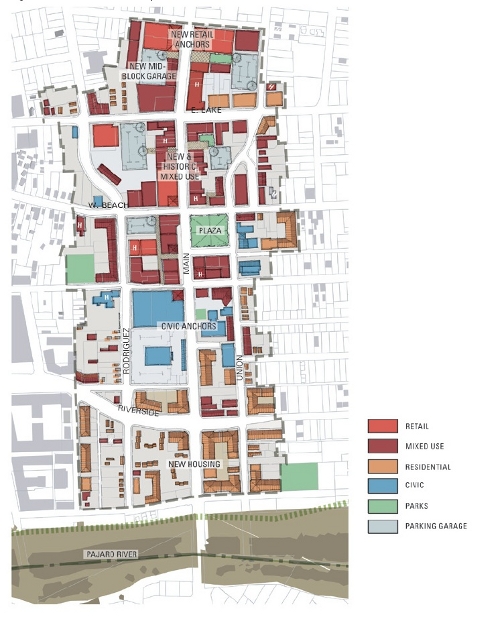

As another way to improve Watsonville’s neighborhoods, VISTA 2030 encourages "infill" development on underutilized land, where blight, vacant lots, single-story buildings, and excessive parking lots do not reflect a property's full potential. Infill development adds vitality on the street and increases patronage of local businesses.

Watsonville's compact and walkable neighborhoods will come about in four basic ways:

- high-density infill within Watsonville's downtown, close to a wide range of shops and regional transit service;

- moderate- and high-density infill along arterial roadways with frequent bus service, through the redevelopment of aging strip commercial;

- new development at moderate densities in the Atkinson and Buena Vista new growth areas; and

- modest intensification of existing neighborhoods, such as with second (or accessory) dwelling units.

VISTA 2030 contains a chapter on "Urban Design & Human Scale," with policies and guidelines that encourage development that is inviting to pedestrians by lining streets with building fronts and entrances instead of garage doors and parking lots. Design objectives are provided for important subareas, such as downtown, along arterial "boulevards," and the urban-agricultural interface. The chapter also encourages a "sense of place" that is rooted in Watsonville's climate and history, and incorporates design features that reflect Watsonville’s hot summers and intense winter rains. For instance, the chapter calls for traditional devices to modulate sunlight (more in the winter and less in the summer) through the use of roof eaves, deeply recessed windows, awnings, and sunshades. Arcades, trellises, and continuous awnings are encouraged in the downtown and shopping environments to give protection from rain in the winter and harsh sun in the summer. Although modern methods, such as heating and air conditioning, could achieve similar goals, VISTA 2030 incorporates more energy efficient and traditional devises to address the local climate, which reinforces a sense of place.

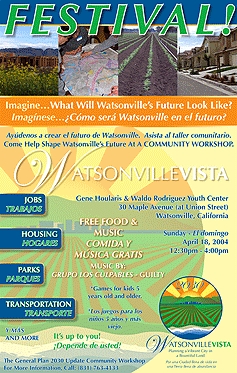

VISTA 2030 was developed through a community-driven process that featured bi-lingual outreach and used community-generated concepts to inform policies. Numerous meetings and workshops shared information and identified community preferences. Presentations at community workshops were translated simultaneously into Spanish and several workshop breakout groups were conducted in Spanish.

Special efforts were made to engage populations that tend not to participate in civic discourse, such as low-income households and immigrants. Glen Bolen, a Principal at Fregonese Associates explained. "We did it by creating a festival atmosphere around public workshops. Music, food and an open informal atmosphere help cross ethnic and cultural boundaries. And we got the word out by ‘branding’ the project by using posters, a logo and an approachable project name, VISTA, which is short for ‘VISion To Action.’"

Weeks in advance of the first and largest community-wide workshop, a steady stream of announcements—in both English and Spanish—were broadcast on local radio stations, printed on posters, advertised in newspapers and mailed to residents. At the first workshop, over two hundred community members worked in small groups to generate land use concepts. Each group was organized to contain diverse view points, and sat at a table with a map of Watsonville and color-coded land-use gamepieces that represented a range of employment, housing and community facility options. Groups grappled with how Watsonville should change as they selected among land uses (at different densities) to meet 2030 employment and housing forecasts.

A large number of Watsonville's Hispanic residents participated in the workshop. To do this, workshop presentations were translated simultaneously into Spanish and several small groups were Spanish-speaking.

An Advisory Committee – with representatives across a spectrum of interests – met monthly and guided the development of the General Plan. A better understanding of issues was gained early in the process through “brainstorming sessions, and by interviewing important stakeholders, such as business leaders, environmentalists and government agencies.

The community-created concepts generated at the workshops identified common themes, framed policy choices, and served as the basis for land use alternatives that were developed by the consultant and analyzed. The results of the workshops were presented to the Advisory Committee before the Committee set the direction of the General Plan's Land Use Map.

Economic Hard Times. "The 2006 General Plan's emphasis on infill is laudable and received support across the board," said Lisa Dobbins, Executive Director of Action Pajaro Valley, "but the Plan has been a victim to both hard economic times [after the financial collapse of 2008] and neighbors fighting development when it's planned near them – one of the main reasons behind the [Buena Vista] lawsuit."

Legal Challenges. "I live out in Buena Vista and I don't want to see it change," said pilot Sam Kennedy in a Santa Cruz Sentinel article. "Grow somewhere else."

The low-density neighborhood of Buena Vista was identified as an area for growth by Measure U. Measure U and VISTA 2030 recognized Buena Vista to be among three geographic areas next to Watsonville that did not contain productive agricultural land – and was therefore considered as suitable for future growth.

Shortly after VISTA 2030 was initially adopted in 2006, the Watsonville Pilots Association, the local Sierra Club, and Buena Vista residents challenged the Plan, holding that the City did not have the authority to remove safety zones around the airport identified by the Caltrans Division of Aeronautics Airport Land Use Planning Handbook and that the Plan should not call for urban densities in Buena Vista -- a portion of which lies along airport flight paths. The lawsuit also held that the EIR failed to analyze an alternative that assumed less overall development, and that it did not adequately analyze regional traffic impacts.

In 2010, a California appellate court agreed. As a consequence, the City rescinded the 2006 General Plan. However, the City Council adopted a new Plan in January 2013 that is nearly identical to the 2006 Plan, except for in regards to Buena Vista.

One of the most negative outcomes of the lawsuit is that rescinding of the 2006 Plan due to the issues involved in the lawsuit has held up implementation of the Plan as a whole. "The innovative strategies in the 2006 General Plan can only be pointed to as they aren't in effect," said Keith Boyle, "and this has made it hard to move forward. For example, we haven't been able to make zoning changes along our strip commercial corridors that would encourage mixed-use development along our transit corridors, even though virtually everyone thought this is a good idea."

The legal challenges surrounding VISTA 2030 bring to light a nuanced tension between community priorities, State planning requirements, and rulings from the Court system. The Watsonville lawsuit illustrates the importance of solving known problems through the public outreach process, because if an issue goes to court, the court may operate under different priorities than those of the community.

Now, pilots and Buena Vista residents are working with the City to arrive at a new land use plan with significantly less development in the Buena Vista area. While some reduction in Buena Vista dwelling units may be appropriate in light of stagnant growth since 2008, the City may find it difficult to accommodate future growth if Buena Vista is not included. Donna Jones of the Santa Cruz Sentinel summed up the challenge: "From the City's perspective, there's little choice but to plan for growth in Buena Vista. The State requires cities and counties to plan for housing to meet population increases, and … [Measure U represented] a compromise with diverse stakeholders to grow [in Buena Vista] rather than on prime farmland or sensitive environmental areas. But pilots and Buena Vista residents share a common interest in retaining the area's character. Pilots fear development will increase safety risks and noise conflicts. Residents worry about traffic and the loss of their rural lifestyles" (Santa Cruz Sentinal, November 10, 2011). The compromise solution reestablishes the safety zones around the airport, but allows limited growth opportunities in the remaining Buena Vista area. The successful legal challenge illustrates that General Plans often cannot merely reflect community-based planning but must work within the legal protections established by the courts as well.

CEQA lawsuits are a very real concern for any General Plan. Watsonville’s experience indicates that it would benefit other jurisdictions to think closely about potential legal challenges when preparing a General Plan because the ramifications of a successful lawsuit can be far-reaching. First, communities should try to avoid lawsuits through their public engagement process. And there should be a careful legal review of a general plan and its EIR before it is adopted. This is especially true when there is known public controversy. To the extent possible, General Plan preparers should make sure they “cross all the t’s and dot all the i's” to avoid a legal challenge that could sidetrack an entire planning effort. When faced with a lawsuit, a jurisdiction runs the risk of losing credibility in the eyes of the community, potentially making community members wary of becoming involved in future planning efforts. In Watsonville, where the planning process involved meaningful collaboration in a socio-economically diverse community, such an outcome could be detrimental.

Background Information

Incorporated in 1868, Watsonville lies at the center of the Pajaro Valley with fields blessed by rich soils and mild temperatures. This small city lies amidst one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world. Historically, agriculture has been the reason for Watsonville's growth.

The agricultural sector is the largest employer in Pajaro Valley, accounting for almost 14,000 jobs (including farm related industry manufacturing). The agricultural economy in the Pajaro Valley is expanding, partly due to a recent shift in crop production to more labor intensive crops, such as strawberries. The Pajaro and Salinas Valleys contains over 10,000 acres of strawberry fields that employ 15,000 to 18,000 primarily immigrant workers from Mexico. According to an Action Pajaro Valley publication, “Watsonville has become the de facto housing and service center for the region's farm labor force.”1

An Urban Limit Line. In response to the increasing growth pressures on Watsonville’s valuable farmland, a coalition of diverse interests joined together and succeeded in passing "Measure U," a voter referendum that established an "Urban Limit Line" (ULL) to protect productive farmland from development. The ULL will also redirect pressures for growth to already urbanized areas: in downtown, along transit-rich corridors, and on land on Watsonville's edge with little agricultural value. In 2002, Measure U passed by 62% of the voters.

Measure U was supported by a coalition of interests and brought together by Action Pajaro Valley, a community non-profit that articulated a shared agenda of managed growth to promote social equity, environmental sustainability and the local economy. Business and labor interests recognized the importance of agriculture to the local economy; and environmentalists and farmers appreciated that sensitive lands would be protected.

Community Description

Location: About 15 miles southeast of Santa Cruz and 45 miles south of San Jose.

Area: 4,240 acres.

Population (2010): 51,199 residents2 and 18,300 jobs.3

The Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments (AMBAG) projected in 2008 that Watsonville's population will grow from 49,571 in 2005 to 62,463 in 2035.4 This represents a reduction of approximately 7,000 new residents from the original AMBAG projections that were in the 2030 Vista Plan.

Ethnicity (2010): Watsonville ranks as the 21st largest Hispanic market in the United States. Approximately 81% of Watsonville residents characterize themselves as Latino and/or Hispanic, compared to 32% in Santa Cruz County as a whole and 38% in all of California.5

Watsonville is also a young town. Children comprise a large part of Watsonville’s population, when compared with other communities. About a third of the population is younger than 18 years.6 Watsonville’s median age has declined steadily over the last forty years, from 33 years of age in 1970 to 29 years in 2010.7 The median age for Watsonville’s Latino population is even lower -- about 24 years.8 For comparison, the median age of California is about 35 years of age.9

Only 55% of Watsonville residents have graduated from high school, compared to 85% in Santa Cruz County and 81% in California.10

Industries & business: agriculture-related business and manufacturing comprise a significant share of Watsonville’s jobs, one factor that precipitated Measure U to protect agricultural lands. An increasing number of jobs are service-related and reflect Watsonville's increasing connectedness to the Bay Area's economy.

Mean Household Incomes (2010): $55,640 in Watsonville compared with $84,883 in Santa Cruz County as a whole and $82,230 in California as a whole.11

Per Capita Incomes (2010): $15,821 in Watsonville compared with $31,169 in Santa Cruz County as a whole and $28,551 in California as a whole.12

Tags: Growing Community, Small City in Rural Setting, Suburban Growth Pressures, Social Equity, Compact Development, Transit-Oriented Development, Open Space Network, Greenprint.

TIMEFRAME OF PLAN DEVELOPMENT: See "Adoption Process and CEQA" below.

KEEPING ON TRACK. The General Plan process began in early 2004 with City Council adoption occurring in May 2006, and took only a few months longer than was planned.

A legal challenge and California Appellate Court ruling (described above) forced Watsonville’s City Council to rescind the Plan in 2010. In the ruling, the Court directed the City to modify certain sections of the General Plan and EIR to comply with state law.

The vision for VISTA 2030 is comprised of guiding principles related to topics such as economic development, Watsonville’s rural setting, housing, and diversity. Each principle is accompanied by a set of related performance goals. For example, the performance goals for attaining the economic development guiding principle include the following, among others:

- Increase number of Watsonville residents employed in Watsonville.

- Improve ratio of jobs to housing.

- Increase job diversity.

CITY DEPARTMENT AND AGENCY INVOLVEMENT. Watsonville’s Community Development Department, led at that time by John Doughty, managed the City’s General Plan effort. Many other City departments were involved during the Plan’s development, including: Parks & Community Services, Public Works, Economic Development, Fire, Police, and Redevelopment & Housing. Several agencies also had an interest in Watsonville’s General Plan, such as: the Pajaro Valley Unified School District, the Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments (AMBAG), State Water Resources Control Board, the State Department of Fish and Game, and the Federal Aviation Administration.

LEGAL AND POLICY CONTEXT. In 2002, Watsonville’s voters were presented with Measure U, which asked: “Shall the City of Watsonville amend the Watsonville 2005 General Plan thereby imposing certain restrictions on growth, […] to define a new Urban Limit Line (“ULL”) and make related changes to General Plan policies and land use designations.”13 In California, local referenda that are consistent with State law must be enacted, and Measure U’s Urban Limit Line took effect through a General Plan Amendment in 2004. The General Plan update process that resulted in VISTA 2030 – and its emphasis on compact growth – was also called for in Measure U, because the 2004 General Plan amendments did not include a thorough strategy for accommodating growth. VISTA’s growth strategy was also made imperative by California requirements for addressing housing through adoption of a General Plan Housing Element, which must be consistent with and supported by land use policies and sufficient land-based capacity.

VISTA was adopted in May 2006 but was later rescinded because of the previously described legal challenge.14 A revised plan was adopted in January 2013.

CONSIDERATION OF REGIONAL ISSUES. VISTA 2030 met growth targets defined by the Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments (AMBAG). The Plan directed growth into pedestrian- and transit-oriented neighborhoods and corridors, resulting in significantly less overall car trips and emissions than if the same amount of growth occurred at lower densities.

VISTA 2030 embodies “best practices” for regional sustainability, as have been articulated later by AMBAG’s draft Regional Blueprint (under consideration as of January 2012). Simply put, AMBAG’s Blueprint calls for local jurisdictions to pair current trends with improving mobility, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, providing housing and employment opportunities, and protecting natural and cultural resources.

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION, PROCESS & COMMUNITY REACTION. See Context and WOW #3 above.

CONNECTION TO CITY BUDGET. Watsonville's General Plan is the basis for the City's Capital Improvements Plan.

ADAPTABILITY.VISTA 2030’s policies are accompanied by measurable performance measures or targets. For instance, success relating to mobility will be measured by a reduction in driving rates (i.e. vehicle-miles traveled per household). The City will also strive to increase the availability of active recreation as measured in acres per person.

Using VISTA 2030, the City will evaluate performance to determine whether to redouble existing commitments, take new action, or change General Plan policies.

ACCESSIBILITY.VISTA 2030 is available online, in a searchable format

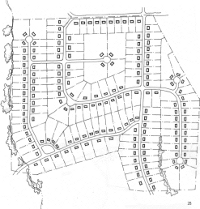

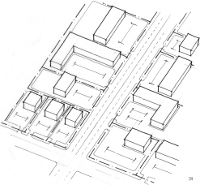

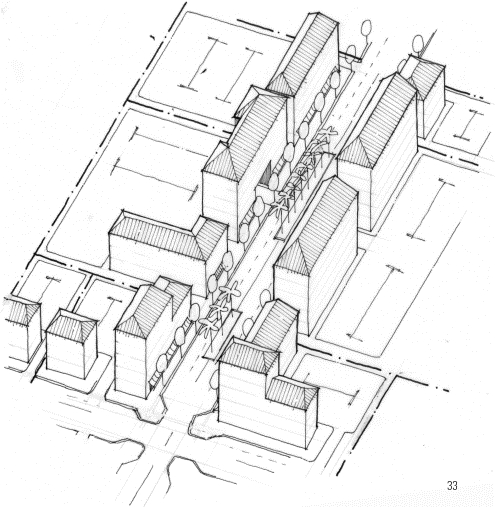

GRAPHIC COMMUNICATION. The 2006 General Plan uses graphics extensively:

- a Land Use Map depicts higher-density development along transit corridors and in downtown, while low-density and open space maintain a clear boundary between urban and rural lands;

- a map illustrates development opportunity areas to better target public and private investments;

- land use diagrams are provided for larger development opportunities; and

- numerous planning diagrams describe planning and urban design concepts.

PLAN ORGANIZATION. VISTA 2030 contains the mandatory General Plan elements. In addition to the mandatory elements, VISTA 2030 also includes the following optional elements:

- Urban Design and Human Scale

- Economic Development

- Historic Preservation

- A Diverse Population

- Environmental Resource Management

VISTA 2030 includes the mandatory conservation element as an element entitled, “Growth and Conservation.” In linking growth and conservation in this way, the City is acknowledging that conservation cannot be achieved without targeted growth. This element addresses the importance of compact development and a clear urban limit as a necessity for preserving Watsonville’s vital agricultural resources.

COSTS AND ACTUAL VS. EXPECTED COSTS. Consultant costs for the 2006 General Plan and EIR cost the City of Watsonville roughly $600,000.

ADOPTION PROCESS AND CEQA. The General Plan update process was initiated in 2003, a year after an Urban Limit Line was established by Measure U. The draft Plan was completed in 2005 and City Council adopted the Plan in 2006. A legal challenge to the Plan was filed in 2006 and an appellate court ruling in favor of the challenge was handed down in 2010. The City Council rescinded the 2006 Plan immediately following the appellate court ruling. The City revised the 2006 Plan to address issues cited by the appellate court and adopted the revised Plan in January 2013.

LEGAL CHALLENGES. See Lawsuit details 15

PLANNING STAFF AND CONSULTANTS. Watsonville’s former Planning & Development Director, John Doughty, played a major role in setting a direction for the VisTA effort (consistent with Measure U). Keith Boyle, current Principal Planner, and Marcela Tavantzis, Watsonville’s Assistant City Manager and Acting Community Development Director, also played central roles during development of the 2006 VisTA and also during revisions necessitated by an Appellate Court decision.16

Fregonese Associates was the lead consultant for the VisTA General Plan effort. John Fregonese was Principal-in-Charge and was assisted by Glen Bolen. Fregonese Associates developed the plan by integrating land use patterns, transportation, and natural resources, through the use of Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping and sophisticated performance modeling.

Matt Taecker, now a Principal at Dyett and Bhatia, was a subconsultant to Fregonese Associates. Taecker helped lead the community facilitation effort and was responsible for policies relating to urban design, natural resources, open space, and recreation.

John Roberts of Theory Into Practice (TIP) consultants served as the team’s economist. Robert’s developed the General Plan’s strategy for protecting and encouraging agricultural- and manufacturing-based jobs.

Jim Daisa, then of Kimley-Horn Associates, guided transportation planning decisions. VisTA’s multi-modal “complete streets” policies encourage the reconstitution of strip commercial corridors into walkable mixed-use boulevards.

Bill Wiseman of RBF Consulting led development of the General Plan’s EIR. RBF is also the consultant responsible for revisions to the General Plan and EIR necessitated by a 2010 Appellate Court decision.17

ACCESSING THE PLAN. Watsonville VISTA 2030 can be accessed online.

Presentations and updates for Watsonville’s VisTA 2030 General Plan can be seen at:

http://www.ci.watsonville.ca.us/departments/cdd/general_plan.html

NAME OF CPR PREPARERS.

Matthew Taecker AICP, Principal, Dyett & Bhatia, San Francisco.

NAME OF PRIMARY POINT(S) OF CONTACT AT THE JURISDICTION. Keith Boyle, Principal Planner, City of Watsonville, (831)768-3050, keith.boyle@cityofwatsonville.org.

DATE REVIEWED BY JURISDICTION. February 2012

CPR PEER REVIEWERS. David Booher, Linda Dalton, Al Zelinka

CPR PROJECT TEAM. Elaine Costello, Project Manager; Co-Chairs Cathy Creswell and Janet Ruggiero; Alexis Mena, Project Assistant

References

- Action Pajaro Valley, At a Glance: An Overview of Issues and Conditions of the Pajaro Valley, available online at http://www.actionpajarovalley.org/publications/, page 35.

- U.S. Census; Census 2010, 2010 Demographic Profile Data; Table DP-1, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (November 14, 2011).

- State of California, Employment Development Department, Monthly Labor Force Data for Cities and Census Designated Places (CDP), September 2011 – Preliminary (Data Not Seasonally Adjusted).

- Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments, Monterey Bay Area 2008 Regional Forecast, available online at http://www.ambag.org/reports/forecast/2008Forecast.pdf, accessed on November 14, 2011, page 57,

- U.S. Census; Census 2010, 2010 Demographic Profile Data; Table DP-1, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (November 14, 2011).

- U.S. Census; Census 2010, 2010 Demographic Profile Data; Table DP-1, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (January 20, 2012).

- Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watsonville,_California, and U.S. Census; Census 2010, 2010 Demographic Profile Data; Table DP-1, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (January 20, 2012).

- Action Pajaro Valley, At a Glance: An Overview of Issues and Conditions of the Pajaro Valley, available online at http://www.actionpajarovalley.org/publications/, page 16.

- U.S. Census; Census 2010, 2010 Demographic Profile Data; Table DP-1, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (January 20, 2012).

- U.S. Census; 2008-2010 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates; Table S1501: EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (November 14, 2011).

- U.S. Census; 2008-2010 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates; Table DP03: SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (November 14, 2011).

- U.S. Census; 2008-2010 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates; Table DP03: SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS; generated by Alexis Lynch using American FactFinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (November 14, 2011).

- Watsonville City Clerk Voter Pamphlet for Measure U, http://www.votescount.com/nov2k2/u.htm

- See: Watsonville Lawsuit Details. All other policies in the 2006 Plan remained in the new General Plan, which was adopted in January 2013.

- See: Watsonville Lawsuit Details. All other policies in the 2006 Plan remained in the new General Plan, which was adopted in January 2013.

- See: Watsonville Lawsuit Details. All other policies in the 2006 Plan remained in the new General Plan, which was adopted in January 2013.

- For information on lawsuit and court decision, see summary by Meyers Nave Riback Silver & Wilson, A Professional Law Corporation, http://www.meyersnave.com/publications/city-watsonvilles-general-plan-update-violated-state-aeronautics-act-and-eir-violated-c

The Catalog

Our catalog contains a number of General Plan "Great Model" examples. Browse the entire catalog

Browse by Principle

- Create a Vision

- Manage Change

- Make Life Better

- Build Community Identity

- Promote Social Equity and Economic Prosperity

- Steward and Enhance the Environment

- Engage the Whole Community

- Look Beyond Local Boundaries

- Prioritize Action

- Be Universally Attainable

Browse by tag:

awards city climate-change context county equity graphics growth-management health implementation infill mature-community organization participation preservation redevelopment region rural smart-growth suburban sustainability town urban urban-design web-strategies